Not that a Humphrey constantly on the road for the past five years would have been unable to assemble and record the nine additional cuts of Funkin’ Just for Fun he’ll release from 7 to p.m. Friday, Aug. 29 at Mother Stewart’s, where he debuted the title cut in April.

Admission will be free and discs, which include the title cut, will be sold for $10.

Tightly packed in the past five years have been the fire that destroyed Humphrey’s old home recording studio; the move to a new house; and the time needed to set up another studio in the basement there – in short, all the grunt work required before the mixing and mastering could conclude.

While describing the disc as “a mixture of original funk, jazz (and) samba” (a formula familiar to fans) the disc’s musical moods swing 360 emotional degrees from the title cut’s “Funking Just for Fun” to the earthshaking power of the Old Testament God in “Yahweh the Truth” to the silly slapstick of “Bird Song,” a funk-infused cover of the 1940 Cab Calloway swing hit, “A Chicken Ain’t Nothin’ but a Bird.”

The last of these tips a hat to one of the three famous Black musicians recognized on the collection, a guy introduced to a later generation as Curtis the custodian, who counseled Jake and Elwood Blues after their yardstick slap-down by Sister Mary Stigmata in Blues Brothers.

At the piece’s end, the trio of drums, sax and bass makes room for a vocal from a chicken that conjures up the notion of the good sister slapping Humphrey upside the head as he swears to God that no chicken was harmed in the making of the disc.

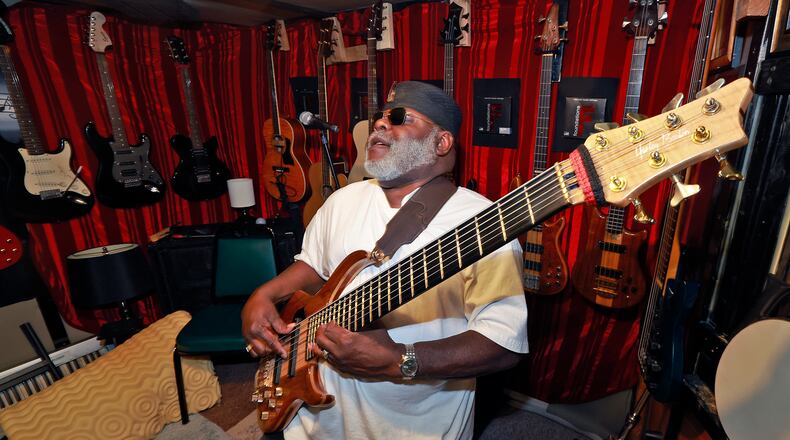

In a collection in which he says “there’s a story behind every song,” “Don’t Fret” involves the fretless bass that usually hangs on the wall of Humphrey’s studio. In the song, it sits on the tonal basement steps and carries on a back-and-forth with higher pitched instruments a few steps up the scale.

While the notes in “Don’t Fret” slide off the strings as smoothly as a plastic puck crossing an air hockey table’s surface, Hump’s thumb turns into Thor’s hammer on “Thum Pit,” bending as many notes in a single take as the combined bass players managed in nine seasons of Seinfeld.

Funk finds a pleasing common ground with rap in “Gimme dat.” While the vocal track stings like a bee, the funk of the rhythm section floats like a Jurassic butterfly and provides a pleasing lyrical alternative to those left weary by the ceaseless flat thwack of a bass drum.

Another unlikely pairing emerges in “James Brown Meets Stanley Clark." Here, the raw and raucous spirit of the Godfather of Soul (and maybe Great-Godfather of Funk) meets the refined renderings of a man whose very hand position on the jazz bass is shaped by foundational work on the standup orchestral bass.

Clarke’s association with the classic jazz masters like Chick Corea are a part of a broader musical reputation that matches a personal reputation the NAACP considered when tapping him as to tap Clark as the spokesman in a current membership campaign that hopes to rally resistance against the current powers that be.

Those unfamiliar with Clarke or Calloway can, of course, find scads of material online. But Humphrey makes that unnecessary in the case of Oscar Brown, Jr., whose voice recites his original poem in the cut “Being Black."

More than two decades after its release, the pointed lyrics and impassioned tones of Brown’s poem I Apologize retain power to wake all but the politically slept with stanzas like this: “I apologize for all I gave; For letting you make me yo’ slave; and going to my early grave, yes, I apologize.”

Behind those words, Humphrey and the band provide a call-and-response between Caribbean groove and the muted jazz of the late-night Harlem Renaissance and, later, Miles Davis.

Chill, muted jazz also warms the air of “Lay It on Me," a slow-walk through a carpeted, candle-lit dining room on a romantic night on which the finest after-dinner treats won’t come from the dessert tray.

Finally, there is “It just came 2 me," the musical statement of a liner note that dedicates the disc “to all friends and loved ones who have passed on.”

Like the bits of conversation on the track, it is a cocktail that stirs the sweetest of memories and bitterest of losses, including the passing of three musicians who contributed: Guitarist Danny Smith and vocalists Jimmy McGee and Paulette Embry.

Other contributors include Michael Kahn and Reggie Harmon, saxophone; Tommy Whitt, guitar; Kevin Hagans, violin; Mike Wade, trumpet; Humphrey, everywhere; Cleve White’s readings; and backup vocals by Ken Dale and Humphrey daughters Christina Odom, De Aunna Sparks and, Audreana King.

What they together produced makes it clear that there’s more to Humphrey music than funkin’ just for fun.